The mention of Nektar in the “Bits & Pieces” chapter leads me to a special aspect – if you’d like, call it an excursion: The record cover. Of course, records need to be bagged. But for a long time, what was on the bag wasn’t important because you had to ask the shop assistant at the record store’s counter the following: “Do you have XYZ by singer ABC?”, and the shop assistant took the record out of his shelves and handed it to you. Later, this changed. The shelves became open so the customer could leaf through the records and search for themselves. From this moment on, the importance of sleeves grew. However, 45s simply came in neutral sleeves for a long time, with the record company’s logo or some musical graphics and a hole, so you could read the print on the record label. Only the 45s that were seen as (potential) hits got a cover with track titles, name, and – usually – a photo of the artist(s).

Longplayers were bigger, so their covers had more to offer. While album cover graphics were already seen as important in the U.S. and U.K. around 1966, in Germany, it took a couple of years until record companies figured this out. It was not that German albums didn’t have any sleeves – of course they had them, but they usually didn’t show much more than the 45s – simple but very colorful photos of the artists, combined with arbitrary Letraset typefaces. The stylish ECM or MPS sleeves were an exception. It was not until the early 1970s that some (not all) German record labels discovered the sleeve as an important part of album presentation that could help in selling a record.

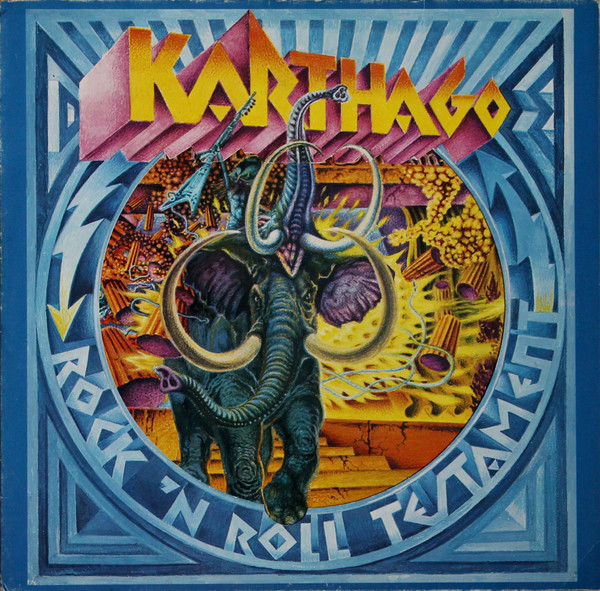

Among the first labels caring about this was Bellaphon of Frankfurt, along with its sublabel, Bacillus. Most Bacillus acts had their record covers made by the same graphic artist, holding a certain “corporate style” this way. The name of this artist is Helmut Wenske. His works have always been discussed in a controversial way – let’s see why.

Helmut Wenske of Hanau (near Frankfurt) was a remarkable artist in his own right. Born in 1940, he has no memory of when exactly he started drawing, but, as he says, he did it from an inner need to be able to cope with himself and the world outside around him without going crazy. At the beginning he got into trouble with his mother because she saw what he drew as incorrect, “done in the wrong colors”. He became a porcelain painter, and in the mid-1960s he worked as a decorator at a Hanau department store. Part of his job there was to paint giant façade posters, a skill that became useful for him later when he lived in an apartment above a brothel: He made a good part of his living with decorative, pornographic paintings there, as well as at the striptease bars of Hanau’s red light district.

Bellaphon hired him as an in-house graphic artist. He designed more than 100 record sleeves for Bellaphon and its sub-labels, Bacillus and Admiral, for 45s as well as for albums. Most of his cover designs were rather unexceptional, especially the ones for 45s: “This job didn’t have much to do with painting. I huddled layouts together, out of three or four crappy slides of the artist I selected the best one, decided on colors and fonts, hammered ads together and plunked down some copy texts to get out of this loony bin as soon as possible.”1

Independently, Wenske also worked with oil and topcoat paint, he did oil paintings, gouaches, and pencil drawings. He developed a style one could immediately recognize. Especially in connection with Nektar, he started using these works also for cover illustrations – at least five of his paintings were used for Nektar album covers between 1972 and 1975; he also drew the “Nektar Man” that became their signet (a felt pen drawing, 96 by 48 cm, originally titled “Hermaphrodit”, 1972; the original is lost).

These paintings were not the easy kind of stuff. Their characteristics were detailed precision, dreamlike distortions of perspective, overflowing optical illusions mixed with intricate surreal figures and horror motifs, often with sexual connotations. In many paintings, even more in his monochrome pencil drawings, you find faces everywhere, but often have to look twice to realize them. You are welcomed to enter illogical worlds between melting and breaking, lava and mold. There are rarely moments of relaxation in his paintings (except in some of his self-portraits), usually their atmospheres are characterized by turmoil, covered with endless bleakness. Characters you see are mostly sad-faced or panicking, or there are hidden faces; when you become aware of them after a while, they stare maliciously and aggressively. One probably doesn’t do him wrong when guessing that, by painting these sceneries, Wenske had tried to come to terms with some derailed LSD experiences. (He wouldn’t be the only one. H.R. Giger developed his “Alien” characters the same way.)

It was a creative kick that lasted for around five years and, at times, must have been extreme. “Sometimes I painted around the clock, for days and nights on end, driven by inner visions that I often put unconsciously down on paper.”2

Wenske also provided illustrations for science fiction books, released by the renowned Insel-Verlag. Among the books he contributed to are German editions of books by StanisławLem and Philip K. Dick, and he won several science fiction reader polls as best graphic artist.

Between 1971 and 1976, Wenske published a series of posters, a wall calendar, and a couple of art books, the latter usually introduced by pompous essays. At least one of these books (“Ahasverus”, 1973) features (piss-poor) self-penned poems and prose. He also had a handful of solo and group exhibitions which were reviewed by a few serious papers, like the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

In the art book “Gesichte des Athanasius Pernath” (Visions of Athanasius Pernath, 1977), a cycle of nine portraits connected to Gustav Meyrink’s novel “Der Golem”, Wenske’s paintings became more subtle. The colors became palish, but the subjects were still far from being gemütlich. “Letzte Aufzeichnungen aus der Somnambulanz” (Last Notations from the Somnambulance, 1979) followed, without comments showing black and white pencil drawings. From page to page the lines become thinner and thinner. In the end, a white page with a single tree (or is it a face? a brain?) in the upper right corner is all that remains. “Luckily, by the end of the Seventies the tension faded away, when my painting became more colorless, the objects, as if affected by a cancer, dissolved, everything got reduced to a line and ended in a dot. I was free!”3 It remained Wenske’s last art book.

Under the pen name Chris Hyde, he also published a couple of books about the rock‘n’roll scene of Hanau, which he knew quite well. I don’t know most of these books, but the main topics of the ones I’ve read seem to be smacking someone in the gob, drinking, pissing, fucking, puking, and pretending to be the most dangerous guy on the block. They prove, again, that writing is not Wenske’s strong point, but some readers seem to think that just this gives them an air of authenticity.

Wenske, undoubtedly, knows how to paint. But despite the handful of exhibitions he had, he was never able to reach a long-lasting place within the serious art market. I don’t know whether this has ever been an important goal to him, but the buckets of malice he pours out in his books over all these incompetent critics, essayists, record company folks, former supporters, and other idiots, indicate a harsh, high degree of disappointment and embitterment towards them.4 But it’s not my job to speculate about this.

Wenske took up a day job at a logistics company and spent a lot of his free time with horses. For three years, he was under suspicion of murder until a newly developed DNA test method verified that he couldn’t be the culprit. In 2009, he appeared in the documentary film Roll Over Hanau5 as a contemporary witness. Today, most of his works are his own or in private ownership. The URL of his webpage is for sale, he also had a Facebook page, but it’s gone. Via eBay, you can buy sets of his old returned posters for little money. Sometimes, one of his art books comes up – usually they were numbered and signed as limited editions or came with a signed serigraphy, but this doesn’t seem to increase their current prices.

Dozens of Bacillus and Bellaphon records between 1971 and 1975 got the Wenske treatment, and his graphics became a bit of a cult thing among hard rock fans after a while. He was, in a sense, for Germany what Roger Dean or Hipgnosis (Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell) were for England. But their illustrations were made for record covers, while several of Wenske’s works were “liberal arts” and originally not earmarked. So, the problem with many of them was that his paintings showed horrific scenes, and with regards to their content, they had no connection to the records they were used for. Not every band was completely happy with this.

However, when I was around 15, Wenske’s cover paintings and posters gave me my first exposure to surrealism. They were a sort of starting point to discover art genres that were new to me – thanks for that, Helmut.

If somebody still asks what his story has to do with this book, the answer is: Helmut Wenske is part of the history of German rock. Whether you like it or not, with him, the covers of German rock records became a sort of practical artwork.

There were not many artists doing record covers with a style that was immediately identifiable.

Besides Helmut Wenske, I would like to mention Swiss artist Urs Amann, also a surrealist, who designed several of Klaus Schulze’s records between 1972 and 1975, most famous of which is probably the Timewind cover (1975).

Another artist worth mentioning is Petrus Wandrey (1939-2012) of Dresden. He studied design in Hamburg where he stayed for the rest of his life, except for a short time when he was appointed to WDR TV in Cologne where he created the production design of Brandstifter6 (Arsonists), an early TV movie about the beginnings of the “Red Army Faction”. His main work includes paintings, sculptures, installations, furniture, and jewelry design. To earn money for his liberal arts projects, he started doing cover designs for the magazines Stern, Spiegel, and Playboy, and book illustrations and posters for some Fassbinder films. As a fan of the Dada movement, Warhol’s Pop Art, and Dalí’s surrealism, he developed a style somewhere in the midst of all this, but his individual fingerprints are obvious. In the 1970s, he finished around 40 record covers for rock, jazz, and classical records, usually signed “Wandrey’s” or “Wandrey’s Studio” (which was in fact only him). Among the rock album covers are several for Doldinger’s Passport, but there are also Can’s Monster Movie (apparently with a little help from a comic panel from “The Mighty Thor” by Jack Kirby7), Guru Guru’s Don’t Call Us – We Call You, Grobschnitt’s Jumbo, Scorpions’ Lonesome Crow and Fly To The Rainbow, and several more. His work for record covers ended in the 1980s when he discovered plotters, video, the Quantel paintbox, and computer graphics.

Also worth mentioning: Peter Geitner, working for Kaiser’s Cosmic Music; Barbara and Burkhart Wojirsch, Dieter Rehm, and other style-defining graphic artists and photographers working for the ECM label; Albert Oehlen (Mirror Repair by Gastr Del Sol); Gerhard Richter (his painting “Candle” for Sonic Youth’s Day Dreaming is famous today), Wolfgang Tillmans (3 Weeks by Tiga), Reinhard Hippen for Ohr and Pilz, Beuys and Richter student Emil Schult (Kraftwerk covers), Edgar and Monika Froese (Tangerine Dream covers and photos), Dieter Moebius of Cluster, and a couple more. But most record covers were designed by nameless graphic artists, most of them employees of a record company. And most of their covers looked like that.

1 Wenske 2003, p. 142

2 Wenske 2003, p. 131

3 Wenske 2003, p. 131

4 Cp. Wenske 2003, p. 124, 133, 142 and some more pages

5 Cp. Czarnecky/Siebert 2009

6 Brandstifter, Germany 1969, directed by Klaus Lemke

7 Cp. Kirby 1966